Letter from the Editor: Where We're From

Ho Lin

Let me tell you about what I’ve been up to…

When a letter from the editor starts this way, the usual impulse is to wince (unless you’re reading a travel magazine, in which case yes, Tell us about the wonderful places you just visited, and even then we entertain a bit of jealousy). Shouldn’t we be talking politics, polemics, the wide wonderful crazy world around us? Autobiography in an editorial just seems narrow, egocentric, another symptom of the Selfie Age. Yet here we are, violating the rule.

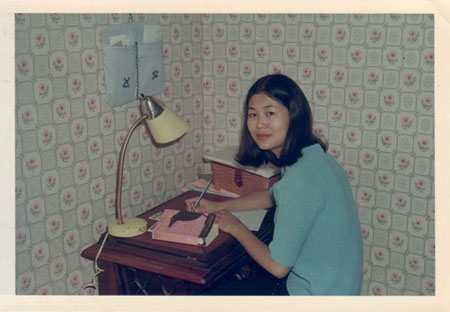

What I’ve been up to is memorializing my mother. She passed away a few months ago. It was not unexpected, though the very end was surprisingly quick. Her passing is important, because like all of us here, she loved her literature. I have an early photo of her when she was living in Baltimore, freshly married to my dad, turning to look at the camera from her desk, an Edgar Allen Poe omnibus at her side, in the act of writing. Many times when I was young I would be in the room while she sat and wrote, and I didn’t mind because I was reading a book myself, both of us occupied with words on pages. You could argue that I was fated to be a writer from the womb – it’s been said that Mom was on a mystery-reading binge when she was pregnant with me. One of my earliest memories is looking at the rows of Rex Stout books on her shelves with juicy titles like Prisoner’s Base and The Black Mountain, gazing at those pulp-tastic covers with knives and bloody skulls and smoking revolvers, and imagining scenes, if not whole stories, around those images.

She wasn’t just into genre, though. All the classics were accounted for, everything from Shakespeare to Fitzgerald to Anaïs Nin. She was a chronicler too: scrapbooks, journals, travelogues (a bit of which you will read in this issue). She was also a writer, although she would never claim she was one. She published two books: Grandmother Had No Name, a study of the changing role of women in modern China which also happens to be a telling of her personal story (there you go, you can be edifying and intimate at the same time), and The Pagoda Mystery, a historical Judge Dee-style mystery novel that she wrote in three days (that she accomplished this feat the same week my car was towed and my short story soundly razzed at my writing workshop was a useful lesson in ego). She would say these works were larks, just something to spend some energy on outside of her life’s work; that fact doesn’t lessen their value.

As the Chinese would say, she lived in interesting times. Born in China during World War II, forced to move with her family to Taiwan in 1949, relocating to the US for graduate school with a few hundred dollars to her name, working in a hospital in inner-city Detroit (fearsome even back then) to pay the bills. She was always calm, always methodical. But it wasn't all logic and pragmatism with her -- she was into qigong and herbal medicine, too. You would never see outward shows of passion – maybe a catty bit of irritation here or a quick burst of laughter there, but these were just sparks, gone like a shooting star. She disapproved of fools but somehow always managed to suffer them (and avoid them) with grace, a talent that came in handy when dealing with some of my friends. (I always tended more towards the Nick Carraway model, with the attendant happy surprises and disasters.) Above all, she was an open-minded observer: of people, of society, of difference and change. She had what all great writers have: the ability to both engage and reflect. Someone I would see as just a cabbie was to her a source of intel, a data bank of cultural knowledge, a person with a story. As an immigrant, a successful stranger in a strange land, she had a perspective about where she was from and where she was going that was unique. Her essay “Scattered and Gone” in this issue is an illustration of that perspective.

A few weeks before her passing my mother had a quick vacation in Ireland, homeland of James Joyce, for the first time. She summed up her travelogue, the last bit of writing in her life, thus: "One’s mind and spirit can carry one to a place where there is no pain, no fatigue, and no illness, but lots of small discoveries. Most of all, it’s the realization that the world has gone on for centuries by itself, with others involved in the changes, no thanks to you. You are at once insignificant and an important witness to a world outside your sphere of experience. Yet even the exotic can be familiar, for human experiences share more similarities at their core. The exchanges with other scholars, strangers you meet on the road, are more precious because you would not have had the experience without the trip, and your understanding is thus enriched. I leave with appreciation and gratitude, carrying this glow of shared humanity all the way back to Chapel Hill." Today my mission is to finish reading all those Rex Stout novels (up to #20 at the moment). Her mission in life was to witness, to document – and it is also our mission in literature. It’s what we’re up to, and where we’re from.

Ho Lin is co-editor of Caveat Lector. More of his work can be read at www.holin.us, and his film criticism can be found at www.camera-roll.com.